Helicopter Stories: Supporting Children with Language Delay

Ggggggrrrrrh, Ggggggrrrrrh, Ggggggrrrrrh, Ggggggrrrrrh,

Ggggggrrrrrh, Ggggggrrrrrh, Ggggggrrrrrh, Ggggggrrrrrh,

He scares the people away. He scares the people in the garden.

My monster is Raah. Then he scares my monster away in the house.

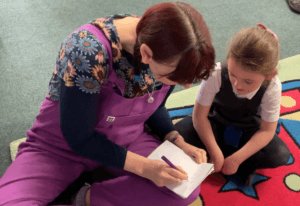

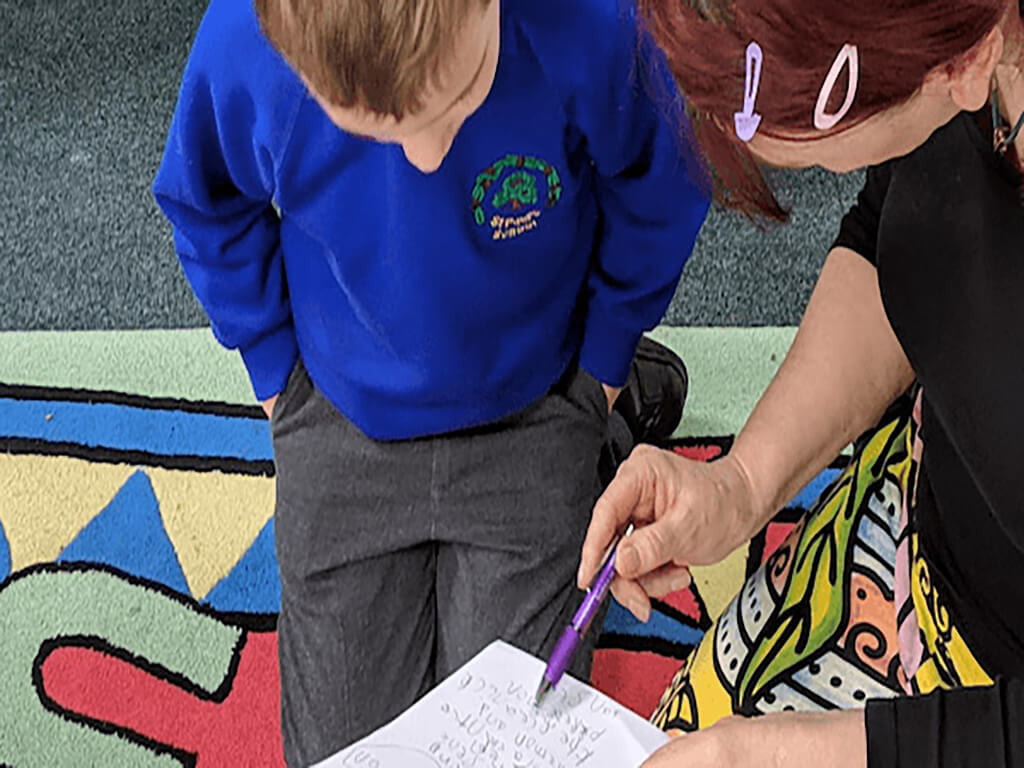

The story above was dictated to me by Zandra (aged 4) during a Helicopter Stories session. Every time Zandra growled, I repeated her sounds exactly as she said them, before writing her story down. The pattern went like this; Zandra growled. I growled back. She put her hands over her ears. We smiled at each other, reassuring ourselves that this was was just a game. Then she looked at the paper I was holding, and watched as I wrote and growled her exact sounds onto the page. Another growl and the pattern repeated. There were eight growl in all, and each was accompanied by exactly the same ritual.

Her teacher sat next to me. She had already informed me that Zandra had delayed language development and that she was a bit shy. Once the growling was over, Zandra smiled. It looked like she had finished, so I placed the A5 paper I was writing her story on, upside down on my lap, thinking my job was done.

But I wanted to know more. I was curious. So I asked a few questions. ‘Zandra, does the growling come from a monster?’ I asked. Zandra nodded. ‘Is that the character you are going to play when we act out your story?’ Zandra nodded again. ‘That’s a great character.’ And then Zandra surprised us all.

She turned the A5 paper back over, looked at where I had written her story and continued to dictate. ‘He scares the people away.’ I repeated Zandra’s words back to her as I wrote them down. And then she was off, telling a story about the monster who scares people from the garden and who is then scared into the house.

The teacher was surprised. Zandra rarely spoke and yet her story is strong, articulate and follows a very clear narrative progression. The monster scares people and then monster is scared away.

We shouldn’t really be surprised. Zandra did what children all over the world are doing. She made up a story. She started from a place that was safe for her, using sounds and growling to communicate her message, and then she found her voice.

I turned the A5 paper I was writing Zandra’s story on over because I never want to drag a story out of a child, because I believe that every story a child shares with me is their gift. It would be wrong to take a gift from someone and to demand more. ‘I like your gift, but I would like it to be longer, more descriptive or a slightly different colour.’ However, I might be curious about a gift. ‘Wow, that is really interesting. What were you thinking when you said that?’

The fact that Zandra found her voice is incredible. The fact that she did it through a story about monsters, and that every time I growled at her she backed away and covered her ears, made me think about how many fears we have to work our way through in order to feel confident enough to share a story with another. This is a brave thing to do, and yet it is something our children are boldly doing every day in their fantasy play.

Seeing the light in Zandra’s face as she dictated to me, was proof of the joy she felt in the telling. Zandra found a meaningful reason to communicate that day.

What better reason is there for finding our voice, than to share a story that will be acted out?

Zandra needed someone who could be ready to listen to her in her own time, just when she was ready. She seemed to have become more confident and ready to tell all of her story. Hope I get my boys to start telling me their stories soon.