Remembering Vivian Gussin Paley (Jan 1929 – July 2019)

“She was always seeing the best in a person, and that starting point usually began with curiosity and excitement about what someone was imagining.”

Gillian McNamee talks about her friendship with Vivian Gussin Paley on the anniversary of her death

In thinking about Vivian, I’m remembering walking into her home. There were large glass windows at the front facing the street with people coming and going, and equally large glass windows at the back looking out onto a yard filled with trees. She watched intently.

My relationship with her began in the classroom as her assistant teacher. Every day my mind filled with questions about what the children were doing, how Vivian saw different situations and how she responded. As we cleaned up at the end of the day, I asked her questions; she talked through the events of the school day until we were walking out the door. Eventually, she said, “Come over on Friday afternoon for tea so we can talk more.” That Friday turned into many Fridays, and sometimes there was a glass of wine after tea, and eventually Shabbos dinner.

Vivian was Jewish, and that was unmistakable in her home. On Fridays, the table was set for dinner, Shabbos candles stood ready to be lit, and there was a loaf of challah under an embroidered linen. There was a sense of ritual to those evenings, and I felt at home being surrounded by preparations. Vivian was a great cook; even her cucumber sandwiches were delicious. Her hospitality extended to anyone and everyone: she conveyed respect, kindness and close listening to all from the very first moment.

In order to understand Vivian, it helps to think about the world she grew up in. She was born in 1929 when our country was going into a deep depression. She was a doctor’s daughter, and Vivian’s view of care and well-being feels unmistakably connected to her parents. As a young girl, she worked in her father’s office, helping patients when they came to get relief from pain and worry. Her father never turned a patient away, even if it was family dinner time. Sometimes people would pay with a dozen eggs or a fresh chicken. Her parents had a deep conviction about how to treat people, regardless of position or finances. The most common prescription included two weeks sipping hot tea in bed. This was a part of the recovery plan for most patients – time.

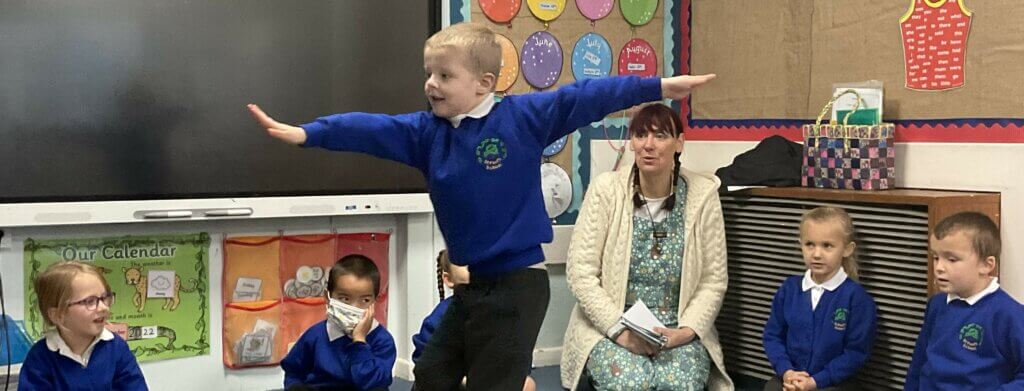

In the classroom, Vivian saw every child and their unique circumstances; she observed with patience and listened. She would give all the time a child needed to come to feeling at home and open to play. She would not rush into the classroom with tasks, a lesson plan or interventions. She was not interested in fixing or pushing the children. Vivian did the opposite – she liked every child, and each child knew it. And she wanted to know what character the child would like to become in pretend play.

I think her sensitivity to children came in part from the experiences of her older brother who was fragile. She saw him teased and bullied at school by other children, and not protected from getting hurt by teachers. She too was misunderstood in kindergarten as a child. Her kindergarten teacher recommended that her mother keep her home for the year as she was shy and quiet. She missed that year in school, and I think she went back to experience it through her decades-long career. When Vivian created her own classroom, she wanted it to be one where her brother – alongside the shy children – would flourish, where each child is accepted and treasured. Our different human tendencies, including bullying and teasing, could be seen, understood and talked about until we figured out how to get along well with one another.

The extraordinary gift Vivian gave me was the opportunity to learn how to be a good kindergarten teacher. She opened my eyes to how a good year in school aged 5 can pave the way to building fair, kind, safe communities in classrooms and cities alike. Vivian wanted to offer children a place where they could learn to be their best selves, addressing problems together and helping to pave the way for their futures. She achieved that by helping every child who walked through her classroom door know that they were special and had a story to tell. She knew that whatever that story was, it would make our world a better place. She began with seeing the best in a person, and the starting point usually derived from one’s imagination.

Did the children need to learn some math each day? Yes. There was no shortage of concepts learned in Vivian’s classroom. But her starting point was different than that of most teachers. She cared first about a child’s new red sneakers, or how fun the stripes were on someone’s favourite shirt, or the story character a child wanted to play out that day. She understood that learning starts with the children’s pretend play. She was lucky that there weren’t people pounding on the door saying, “Did you teach those alphabet letters today?” Even if there were, she’d say, “Don’t worry, the alphabet letters are front and centre alongside the issues we are working on.” Vivian listened to the children. It was called learning and she made it spectacular.

I remember going to her house one afternoon to have tea. Crows came by her yard. They set up a noisy course flying from the telephone poles and on to the electric lines. Vivian started telling me how social they are. She pointed out who was talking to who and how they really looked after one another. I thought, “How does she know all this about crows?!” But then I realised – it’s just like with children. Vivian noticed how the children come and go and who’s talking to whom and the flight patterns they take. Where I just saw crows, Vivian looked deeper. She was attuned to the natural world; a doctor’s daughter ever curious about how all beings live and grow.

Responses